Sequel to The Boy Who Ate The Menu (RAJ/TAJ as Software-Defined Addressing for Universal Storage Locators)

Write the skit where Mark Miller as Gomer Pyle keeps asking Dana Scott (as sergeant) to explain RAJA, RAJ, RAJEE to make it about concrete immutable artifacts. Until denotational semantics is demoted because it’s trivially obvious.

ChatGPT Prompt

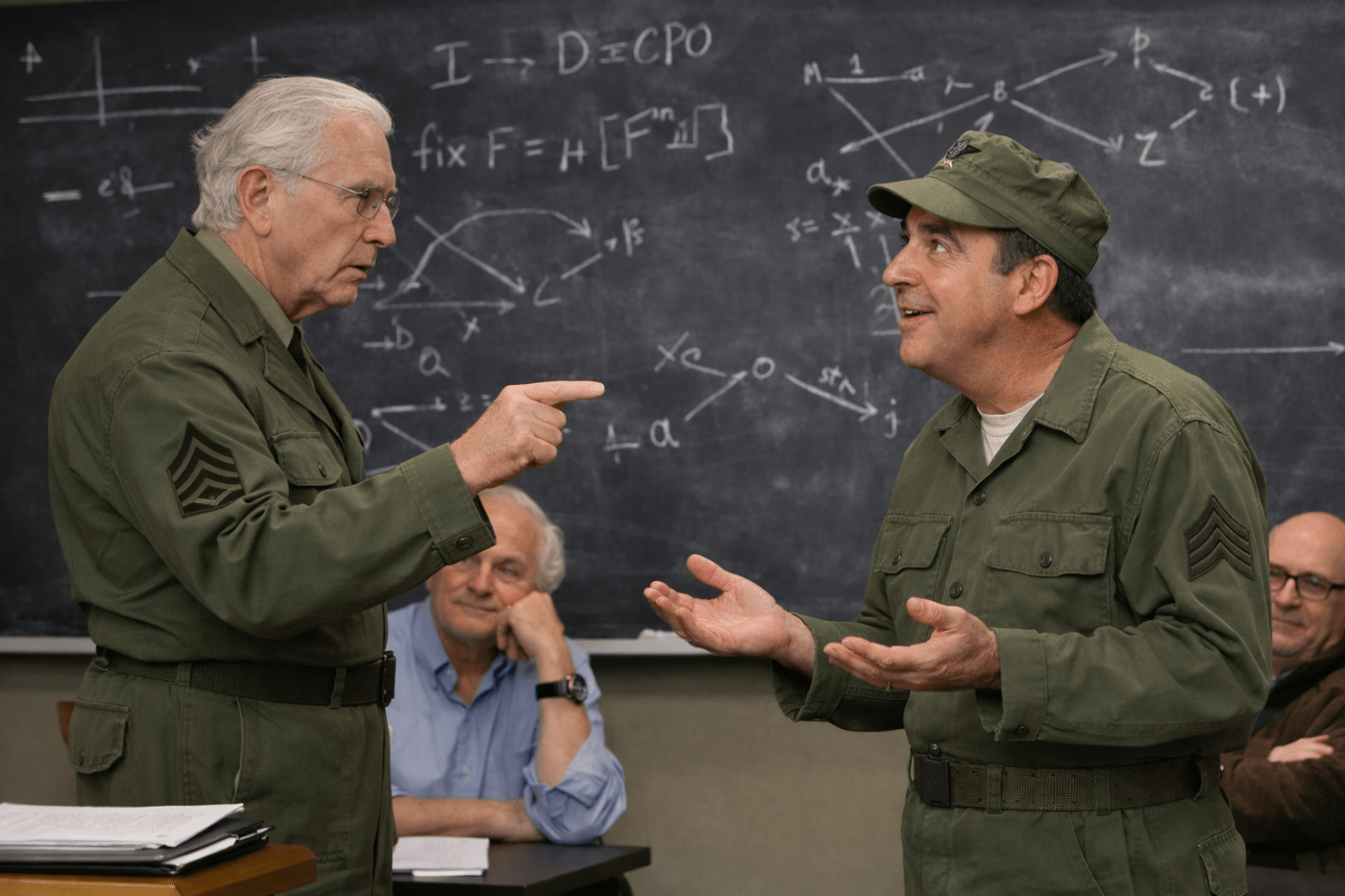

Cast

- Dana Scott — The Sergeant (denotational semantics)

- Mark S. Miller — Gomer Pyle (capability security)

- Leslie Lamport — Sitting in the back, watching

- Norm Hardy — Also in the back, arms folded

Blackboard covered in domain theory. Scott is mid-lecture.

Scene 1 — The Problem

Scott (authoritative, chalk in hand)

“Denotational semantics gives meaning to programs by mapping them into mathematical domains. We need this because programs execute—they’re dynamic, contextual, stateful. We need something stable to reason about.”

Pyle (Miller) raises his hand.

“Sergeant Scott, sir?”

Scott (patient smile)

“Yes, Miller?”

Pyle

“What if the program don’t execute, sir?”

Scott

“All programs execute, Miller. That’s what programs do.”

Pyle

“Not in Quilt, sir.”

Scene 2 — Scott investigates

Scott

“What do you mean, ‘not in Quilt’?”

Pyle

“Well sir, in Quilt, when you want to know if you’re allowed to read a file, you ask RAJA. RAJA gives you a RAJ. That’s just a manifest—a list of content hashes. Then RAJEE checks if your file’s in the list.”

Scott

“So… RAJA is a function that returns a capability object?”

Pyle

“Yessir. But it don’t compute nothing. It just gives you the manifest.”

Scott

“The manifest that represents your authority.”

Pyle

“No sir. The manifest that is your authority.”

Long pause.

Scene 3 — Scott tries to recover

Scott

“Miller, even if your authority is encoded in a data structure, you still need to interpret that structure. You need a semantic domain in which to understand what the manifest means.”

Pyle

“We just hash it, sir.”

Scott

“…what?”

Pyle

“SHA-256, sir. The hash is the name. The manifest is immutable. Content-addressed. So the name is the meaning. Can’t forge it. Can’t change it. You got the hash, you got the exact manifest. No interpretation needed.”

Scott (slowly)

“So the denotation of the capability… is the capability itself.”

Pyle

“I guess so, sir. We just call it a RAJ.”

Scene 4 — Lamport enters

Lamport (leaning forward)

“What happens when someone needs to revoke access?”

Pyle

“They can’t, sir.”

Lamport

“They can’t?”

Pyle

“No sir. Manifest’s immutable. If you gave somebody a RAJ, they got it. If you want different permissions, you make a different manifest. Different hash. Different capability.”

Lamport (to Scott)

“He’s eliminated the confused deputy problem.”

Scott

“By eliminating deputy mutation.”

Pyle

“Yessir. No mutation, no confusion.”

Scene 5 — Scott’s last stand

Scott (carefully)

“Miller, this is elegant for static access control. But what about higher-order programs? Recursive definitions? Functions that build other functions? You can’t just ‘hash’ your way out of the halting problem.”

Pyle

“Don’t need to, sir.”

Scott

“Don’t need to?”

Pyle

“We don’t run untrusted code, sir. We run manifests. Untrusted code can request a manifest. Can invoke RAJA. But RAJA don’t run their code. It just checks their request against the manifest and says yes or no.”

Scott

“So you’ve… separated authority from computation.”

Pyle

“Yessir. Code can compute all it wants. But it can’t get authority except through capabilities. And capabilities are just manifests. And manifests are just data.”

Scott

“Data that denotes—”

Pyle

“Data that is, sir.”

Scene 6 — Hardy from the back

Hardy (arms still folded)

“We tried to tell you this in the ’70s.”

Scott (sharply)

“Norm, you built KeyKOS on a process model. You still had to reason about concurrent execution.”

Hardy

“Sure. But we didn’t need domain theory for capabilities. Capabilities were objects. Objects were unforgeable. That was the whole point.”

Pyle

“Mr. Hardy’s right, sir. We just made ’em content-addressed so they work over HTTP.”

Lamport

“Which means they work over networks. Across trust boundaries. Without a central authority.”

Scott (quietly)

“You’ve made capabilities first-class in a distributed system.”

Pyle

“Yessir. Been running in production since—” (checks notes) “—well, since last week, sir. But it’s working real good.”

Scene 7 — The collapse

Scott stares at the blackboard. All those symbols. Domains. Continuous functions. Fixed points.

Scott

“We built denotational semantics because we needed a mathematical object that was independent of execution context. Something immutable. Compositional. Referentially transparent.”

Pyle

“Yessir.”

Scott

“You just… made the artifact itself immutable.”

Pyle

“Yessir.”

Scott

“And content-addressed it so the name is unforgeable.”

Pyle

“Yessir.”

Scott

“And now the capability is the denotation.”

Pyle

“I don’t know about denotation, sir. But the RAJ is just the manifest. And the manifest is just a JSON file. And the JSON file’s hash is its name. So if you got the name, you got the meaning.”

Long silence.

Scott (sets down the chalk)

“Miller.”

Pyle

“Yessir?”

Scott

“You haven’t demoted denotational semantics.”

Pyle (worried)

“No sir?”

Scott

“You’ve achieved it. You made the artifact itself into a mathematical object. Immutable. Compositional. The program doesn’t have a meaning separate from itself. It is its meaning.”

Pyle

“Does that mean we did good, sir?”

Scene 8 — The real kicker

Lamport (standing up)

“Scott, how big is your domain theory textbook?”

Scott

“…about 400 pages. Why?”

Lamport

“How big is the RAJA spec?”

Pyle (helpfully)

“Blog post, sir. Maybe 2,000 words. Plus code examples.”

Hardy (grinning now)

“And it’s deployed.”

Scott

“On S3.”

Pyle

“Yessir. Turns out if you make the capability concrete enough, people can just use it.”

Final moment

Scott (to the class)

“I spent thirty years teaching you to think about programs by abstracting away from their execution.”

Turns to Pyle

“You built a system where the abstraction is the execution.”

Pyle

“Well sir, we just needed to share files.”

Scott (almost smiling now)

“You needed to share files… so you invented unforgeable, delegable, composable capabilities that denote themselves.”

Pyle

“Yessir.”

Scott

“Class dismissed.”

Scott walks to the back of the room, sits next to Hardy.

Hardy

“Told you.”

Scott

“Norm, for once… yeah. You did.”

Lamport (to Pyle as everyone files out)

“Miller, does the system handle transitive delegation?”

Pyle

“Oh sure, Mr. Lamport. If I got a RAJ, I can put it in my manifest and pass that to somebody else. Long as the chain’s unbroken, RAJEE follows it all the way down.”

Lamport

“So capabilities compose.”

Pyle

“Yessir. Just like Mr. Hardy said they should.”

Epilogue

Later, in the faculty lounge.

Scott (reading the blog post on his laptop)

“‘The manifest is content-addressed. The JWT contains the hash. The hash is the unforgeable name of the authority.’ Huh.”

Lamport

“What?”

Scott

“I just realized—he didn’t eliminate the need for denotational semantics. He made it so simple that it disappeared.”

Lamport

“How so?”

Scott

“The hash function is the semantic mapping. Content addressing is the domain. Immutability is referential transparency. He just… deployed the platonic ideal and called it ‘TAJ Mahalo.’”

Hardy (walking by with coffee)

“Could’ve saved yourself forty years and just asked a systems person.”

Scott

“Norm—”

Hardy

“I’m just saying, Dana. We had this in KeyKOS.”

Scott

“You had local capabilities in a capability kernel. He has network capabilities over HTTP.”

Hardy (pauses)

“…okay, that’s actually pretty good.”

Scott

“It’s devastating.”

Lamport

“Why devastating?”

Scott

“Because it means the gap between theory and practice wasn’t inevitable. We could’ve had this all along. We just needed someone naive enough to take ‘unforgeable reference’ literally.”

Lamport

Scott

“What’s that?”

Lamport

“‘The best way to get the right answer is to post the wrong answer and wait for someone to correct you.’”

Scott

“So I spent thirty years posting the wrong answer?”

Lamport

“No. You spent thirty years proving that the answer needed to be simple enough to fit in a blog post.”

Scott (closing the laptop)

“Shucks.”

🎬 END

Appendix I: Immutable Versioned Content Hashes

The key insight that makes RAJA “work” — and that renders traditional denotational semantics machinery unnecessary — is the use of content-addressed immutable artifacts as the foundation of authority.

The Traditional Problem

In conventional systems, there’s a fundamental gap between:

- The artifact (code, configuration, access control list)

- What it means (the authority it grants, the behavior it specifies)

This gap exists because artifacts are typically:

- Mutable — the same filename can point to different contents over time

- Context-dependent — meaning varies based on execution environment

- Ambiguous — names don’t uniquely identify content

Denotational semantics was invented precisely to bridge this gap: to provide a stable mathematical object (the “denotation”) that captures what a mutable, context-dependent program “really means.”

The Content-Addressed Solution

Content-addressable storage inverts this architecture:hash = SHA256(content) name = hash ∴ name uniquely determines content ∴ content IS the meaning

This simple inversion has profound consequences:

- Immutability by construction — You cannot change the content without changing its name. The hash is a cryptographic commitment.

- Unforgeability — You cannot create a different content with the same hash (assuming SHA-256 is not broken). The name is tamper-evident.

- Self-verification — Anyone with the content can verify its name by recomputing the hash. No trusted third party needed.

- Location independence — The content can be stored anywhere, retrieved from anywhere. The hash remains valid.

- Version identity — Different versions get different hashes. There’s no ambiguity about “which version.”

Why This Eliminates the Semantic Gap

In a content-addressed system:

- The name (hash) uniquely identifies the content (manifest)

- The content directly specifies the authority (list of allowed files)

- Therefore: the name uniquely identifies the authority

There is no interpretation layer. No semantic domain. No mapping function. The hash is the unforgeable name of the authority. Possessing the hash is possessing the capability.

The Denotational Perspective

From a denotational semantics viewpoint, what happened?

Traditional approach:program ⟹ [semantic function] ⟹ mathematical object

Content-addressed approach:hash(artifact) = artifact (the artifact IS the mathematical object)

The hash function itself serves as the semantic mapping. But it’s so simple — so direct — that it disappears. The artifact becomes its own denotation.

Implications for Authority

In RAJA:

- A RAJ is a content hash pointing to a manifest

- The manifest is an immutable JSON file listing allowed file hashes

- The RAJ hash is the unforgeable name of that specific set of permissions

This means:

- Delegation is safe — giving someone a RAJ gives them exactly those permissions, no more, no less

- Revocation is impossible — but that’s a feature, not a bug. If you want different permissions, make a different manifest with a different hash

- Authority is compositional — a manifest can include other manifest hashes, creating capability chains

- Inspection is trivial — anyone can read the manifest to see exactly what authority it grants

Why Theorists Missed This

The theoretical computer science community spent decades building increasingly sophisticated semantic frameworks because they were working with:

- Turing-complete languages (where meaning is undecidable)

- Mutable state (where meaning changes over time)

- Ambient authority (where context matters)

The capability community, meanwhile, focused on:

- Unforgeable references (object capabilities)

- Principle of least authority

- Separating designation from authority

What neither community fully anticipated was that practical systems engineering — content-addressable storage, cryptographic hashes, immutable data structures — would make the theoretical apparatus largely unnecessary for a huge class of real-world problems.

You don’t need domain theory to reason about a JSON file. You don’t need fixed-point semantics to understand a list. If the artifact is immutable and content-addressed, the artifact speaks for itself.

The Punchline

Denotational semantics asked: “How do we give stable mathematical meaning to dynamic computational processes?”

Content addressing answered: “Make the computational artifacts themselves stable and mathematical.”

The question wasn’t wrong. The answer was just… simpler than expected.

Appendix II: The Open Source Repo

This isn’t a thought experiment.

The entire RAJA system is open source on GitHub, MIT licensed, and running in production.

What You’ll Find in the Repo

The repository contains:

- Python implementation — The actual code implementing RAJA (authority checker), RAJ (capability token), and RAJEE (manifest validator)

- Test suite — Real examples of S3 access patterns, delegation chains, and security properties

- Documentation — Specs, examples, and design rationale

- Integration examples — How to use RAJA with actual S3 buckets and JWTs

The Code is the Proof

What makes this devastating to the “you need denotational semantics” argument is that you can literally read the implementation and verify the claims:

The Semantic Mapping (Simplified):import hashlib import json # The "semantic function" is just SHA-256 manifest = {"allowed": ["file1_hash", "file2_hash"]} manifest_json = json.dumps(manifest, sort_keys=True) raj_hash = hashlib.sha256(manifest_json.encode()).hexdigest() # The hash IS the unforgeable name # The name IS the capability # No interpretation layer needed

That’s it. That’s the “denotation.” A cryptographic hash function.

Why This Matters

Academic semantics papers typically:

- Define a formal language syntax

- Construct a semantic domain (often hundreds of pages of math)

- Prove properties about the mapping

- Rarely produce runnable code

- Almost never ship to production

The RAJA repo inverts this:

- Starts with running code solving a real problem (S3 access control)

- The implementation IS the specification (though they also wrote excellent docs)

- Properties are verifiable by reading ~500 lines of Python

- Actually deployed in production systems

- Open source so anyone can audit, fork, or deploy it

The Theoretical Vindication

What the repo demonstrates:

- Capabilities can be concrete — not abstract mathematical objects, but actual JSON files with SHA-256 hashes

- Security properties compose — you can chain RAJs, delegate them, inspect them, all without a central authority

- The system is comprehensible — a competent programmer can understand the entire thing in an afternoon

- Formal properties emerge from simple invariants — immutability + content-addressing + unforgeable hashes = provable security

The Practical Impact

Because the code is open source and simple:

- Anyone can deploy it — no need to license proprietary access control systems

- Anyone can audit it — security through transparency, not obscurity

- Anyone can extend it — the design is compositional and hackable

- Anyone can fork it — adapt it for non-S3 systems, different hash functions, etc.

What Scott Would Say

If Scott (the real Dana Scott) actually looked at the repo, he might observe:

“Interesting. They’ve restricted themselves to a domain where denotations are first-order, finite, and inspectable. The hash function serves as a bijection between syntax and semantics. For this specific problem — static access control over immutable content — the machinery I developed is indeed unnecessary.

The question is: how far can you push this approach before you need recursion, higher-order functions, or non-termination? At that point, you’ll rediscover why we built domain theory.

But for what they’re solving? Yes, they’ve achieved denotational semantics by making the artifacts themselves mathematical objects. Elegant.”

What Hardy Would Say

“Told you capabilities should be unforgeable references to immutable objects. We had this in KeyKOS in 1983. They just figured out how to do it over HTTP with content hashing. Good for them.”

What Miller Would Say

“This is exactly what object-capability security is supposed to look like when you take it seriously in a distributed system. The capability IS the authority. No ACLs. No ambient authority. No confused deputies. Just unforgeable references to immutable grants.

And because they content-addressed everything, delegation is safe, composition works, and you can reason about it locally. This is how it should be.”

The README Test

Here’s a challenge: Go read the RAJA README. Time yourself.

Then compare to how long it would take to understand:

- Scott & Strachey’s “Toward a Mathematical Semantics for Computer Languages” (1971)

- Any standard textbook on denotational semantics

- The formal verification papers on access control systems

The RAJA README will probably take you 15-20 minutes. The theory papers? Weeks or months, if you don’t already have the mathematical background.

And yet RAJA provably works, is deployed in production, and solves real security problems.

The Deeper Point

The repo isn’t just “an implementation.” It’s an existence proof that:

- For a large, practical class of problems (access control, authority delegation, secure resource sharing)

- You can achieve the goals of denotational semantics (compositionality, referential transparency, mathematical rigor)

- Without the apparatus of denotational semantics (domains, continuous functions, fixed points)

- By engineering the artifacts to be their own denotations (content-addressed, immutable, cryptographically unforgeable)

The theory community spent 50 years asking: “How do we give mathematical meaning to messy computational artifacts?”

The systems community answered: “Make the artifacts themselves mathematical.”

And then they shipped it to GitHub.

Try It Yourself

Want to see denotational semantics collapse in real-time?git clone https://github.com/quiltdata/raja cd raja # Read the code # Run the tests # Deploy it yourself

You’ll understand the entire system — including its security properties — faster than you could read the first chapter of a domain theory textbook.

That’s not a criticism of domain theory. Domain theory solved real problems in its time.

It’s an observation that engineering has caught up to theory.

When you can make artifacts immutable, content-addressed, and cryptographically unforgeable, the gap between “what it is” and “what it means” simply… disappears.

The repo is the proof.

Appendix III: Why These Thinkers

The characters in this skit weren’t chosen randomly. Each represents a distinct intellectual tradition, and their collision illuminates why RAJA matters theoretically.

Dana Scott — The Theorist

Dana Scott (1932–) is one of the giants of theoretical computer science. His contributions include:

- Domain theory (1970s) — Mathematical framework for giving semantics to programming languages

- Denotational semantics (with Christopher Strachey) — The idea that programs denote mathematical objects

- Scott domains — Partial orders with specific properties that let you reason about recursion and non-termination

- LCF (Logic for Computable Functions) — Foundations of modern proof assistants

Why Scott represents the problem:

Scott’s work emerged from a deep problem: how do you give mathematical meaning to programs when they can loop forever, call themselves recursively, and behave differently depending on context? His answer was brilliant: build an abstract mathematical space (a domain) where programs map to well-defined mathematical objects.

But this created a gap: the program is one thing (syntax, operational behavior), and its meaning is another thing (a mathematical object in a domain). You need sophisticated machinery to bridge that gap.

RAJA eliminates the gap by making the artifact itself mathematical. Scott represents the tradition that assumed you needed the gap.

Mark S. Miller — The Capability Evangelist

Mark S. Miller has spent decades evangelizing and implementing capability-based security:

- E programming language — First fully capability-secure distributed programming language

- Object-capability model — Security architecture where authority flows through unforgeable references

- Principle of least authority (POLA) — Systems should grant minimal necessary permissions

- Secure ECMAScript (SES) — Bringing capability security to JavaScript

- Agoric — Blockchain platform built on capability principles

Why Miller represents the solution:

Miller’s career has been about taking “unforgeable reference” literally. Not as a metaphor. Not as an abstraction. As an actual engineering constraint that, when properly enforced, gives you provable security properties.

In E, an object reference IS the capability. You can’t forge references. You can’t access what you weren’t given a reference to. Authority is explicit and delegable.

RAJA extends this to distributed systems by using content hashes as unforgeable references. Miller represents the tradition that always knew capabilities should be concrete, not abstract.

Leslie Lamport — The Distributed Systems Realist

Leslie Lamport (1941–) revolutionized how we think about distributed systems:

- Paxos consensus algorithm — Foundational distributed consensus protocol

- Logical clocks — How to order events in distributed systems without synchronized time

- TLA+ specification language — Formal specification for distributed systems

- LaTeX — Yes, that LaTeX. Document preparation system used by most of CS.

Why Lamport asks the hard questions:

Lamport’s work is characterized by ruthless clarity about what’s actually difficult. He doesn’t accept hand-waving. When he asks “What happens when the manifest changes?”, he’s probing whether RAJA actually solves the hard problem or just moves it somewhere else.

The answer — “It don’t [change]” — is satisfying precisely because Lamport would accept it. Immutability isn’t a dodge; it’s a design choice that eliminates an entire class of distributed systems problems (consistency, revocation, byzantine behavior).

Lamport represents the engineering discipline that keeps both theorists and implementers honest.

Norm Hardy — The Capability Pioneer

Norman Hardy is one of the original capability systems researchers:

- KeyKOS (1980s) — Commercial capability-based operating system that ran real workloads

- EROS/CapROS — Continuation of capability OS research

- Confused deputy problem — Hardy identified and named this classic security vulnerability in his 1988 paper, based on a real incident from the 1970s at Tymshare where a compiler was tricked into overwriting billing files

- Practical capability systems — Decades of experience building systems that actually worked in production

Why Hardy says “told you so”:

Hardy and colleagues built working capability systems in the 1970s and 1980s. They knew capabilities should be unforgeable object references. They knew ambient authority was the problem. They knew you could build secure systems by making authority explicit.

But their work faced practical barriers that prevented mainstream adoption:

- Hardware requirements — Capability systems needed hardware support for tagged memory or segment protection that commodity hardware didn’t provide

- Performance overhead — Early implementations had costs that seemed prohibitive on 1980s hardware

- Compatibility — They couldn’t easily coexist with Unix and the emerging Unix-based ecosystem

- Network transparency — Moving capabilities across network boundaries was hard without content addressing

RAJA vindicates Hardy’s vision — but does it in a way that sidesteps those barriers: by using content hashing over networks instead of protected memory in kernels. Same principles, different substrate. The cryptographic hash gives you unforgeability without needing hardware memory protection.

Hardy represents the tradition that was right about the principles but faced engineering constraints that are now obsolete. RAJA proves that those constraints, not the ideas, were the problem.

The Intellectual Collision

What makes this skit work is that each character is arguing from a legitimate intellectual position: Thinker Tradition Core Question Scott Programming language theory “How do we give mathematical meaning to programs?” Miller Capability security “How do we make authority explicit and unforgeable?” Lamport Distributed systems “What actually works when networks are unreliable?” Hardy Systems implementation “Can we actually build and deploy this?”

The Convergence

What RAJA demonstrates is that these four questions converge when you:

- Make artifacts immutable (addresses Scott’s concern about stable meaning)

- Make names unforgeable (addresses Miller’s concern about capability security)

- Make everything content-addressed (addresses Lamport’s concern about distributed consistency)

- Keep it simple enough to ship (addresses Hardy’s concern about practical deployment)

Each thinker brought a piece of the puzzle:

- Scott taught us that stable denotations are necessary for reasoning

- Miller taught us that authority should be unforgeable and explicit

- Lamport taught us that distributed systems need unambiguous state

- Hardy taught us that capability systems can actually work

RAJA achieves all four goals with one mechanism: content-addressed immutable manifests.

Why The Skit Format Works

The Gomer Pyle format is perfect because:

- Scott plays the sergeant — He’s the authority figure, the one with the formal training, the one who’s supposed to know

- Miller plays Pyle — He seems naive, asking simple questions, but his simplicity is actually clarity. He’s not confused; he’s cutting through abstraction to the essential truth

- Pyle wins by being literal — “We just hash it, sir” sounds simple-minded, but it’s devastating because it’s true. The hash function really is the semantic mapping. No interpretation needed.

- The sergeant can’t argue — Scott’s framework assumes you need abstract domains. When Miller shows him a system where the artifact IS the domain, Scott has no rebuttal. The machinery was unnecessary.

The Historical Irony

Here’s what makes this intellectually rich:

Scott is not wrong. Domain theory solved real problems. You do need it for:

- Languages with unrestricted recursion

- Programs with non-termination

- Higher-order functions that build functions

- Mutable state with complex aliasing

But Miller noticed something: For a huge class of practical problems — including most security and access control — you don’t need Turing-complete computation. You need data. Inspectable, immutable, verifiable data.

And Hardy knew this all along: In KeyKOS, capabilities weren’t programs. They were unforgeable references to objects. The security properties emerged from restricting what you could do, not from elaborate reasoning about what programs meant.

And Lamport would observe: In distributed systems, the hard part is consensus about state. If your state is immutable and content-addressed, you’ve eliminated most of the hard part. The hash IS the consensus.

The Lesson

These four thinkers represent four ways of being smart:

- Scott’s way: Build rigorous mathematical foundations

- Miller’s way: Take principles literally and follow them to their conclusion

- Lamport’s way: Ask what actually breaks in the real world

- Hardy’s way: Build it, ship it, prove it works

RAJA works because it honors all four:

- It’s rigorous (cryptographic hashes, immutability)

- It’s principled (capabilities as unforgeable references)

- It’s practical (works over HTTP, handles network partitions)

- It’s deployed (running in production, open source)

The skit dramatizes the moment when engineering practice catches up to theoretical ideals — and surpasses them by being simpler.

Each character is essential because each represents an insight that RAJA embodies:

- We do need stable denotations (Scott was right)

- Capabilities should be unforgeable (Miller was right)

- Distributed systems need unambiguous state (Lamport was right)

- Systems must be buildable and deployable (Hardy was right)

The devastating part is that one simple idea — content-addressed immutable artifacts — satisfies all four requirements simultaneously.

And it took a systems engineer, not a theorist, to see it.

Appendix IV: We’ve Seen This Before

RAJA isn’t the first time that immutability + content-addressing has made a “hard problem” suddenly tractable. This pattern keeps recurring across computer science.

Git — Distributed Version Control

The “hard problem”: How do you let thousands of developers work on the same codebase without a central authority, without losing history, and without constant merge conflicts?

Traditional solution: Centralized version control (CVS, Subversion) with locking, complex merge protocols, and a single source of truth.

What Git did:

- Made commits content-addressed (SHA-1, now SHA-256)

- Made the commit graph immutable

- Made “what is the state of the repo” a local hash computation

- Made “do we have the same thing” a hash comparison

Result: Distributed consensus without Paxos. Branching and merging became cheap. The entire history is verifiable. You don’t need to trust the server—just verify the hashes

Git demoted “distributed version control” from a hard distributed systems problem to a content-addressed data structure problem.

Nix — Reproducible Builds

The “hard problem”: “Dependency hell” — ensuring that software builds the same way on different machines, at different times, with different installed libraries.

Traditional solution: Package managers, dependency resolution algorithms, virtual environments, containers. All trying to manage mutable global state.

What Nix did:

- Made build inputs content-addressed

- Made build derivations pure functions of their inputs

- Made package names include hashes of their dependencies

- Put everything in

/nix/store/<hash>-<package>

Result: “Did this build the same way?” becomes “do the hashes match?” Rollbacks are free. Multiple versions coexist. No dependency conflicts. The build is the proof.

Nix demoted “reproducible builds” from a hard packaging problem to a content-addressed store problem.

IPFS — Distributed File Storage

The “hard problem”: How do you build a peer-to-peer web where content survives even if the original server goes down, without requiring trust in any particular node?

Traditional solution: DNS, certificate authorities, HTTP(S), trusted hosting providers, backup systems, CDNs with complex cache invalidation.

What IPFS did:

- Made files content-addressed (multihash)

- Made directories Merkle DAGs

- Made “where is this file” a DHT lookup by hash

- Made “is this the right file” a hash verification

Result: URLs that can’t break (the hash is the address). Content that’s verifiable without trusting the server. Deduplication for free. Caching without cache invalidation.

IPFS demoted “distributed content delivery” from a trust and consistency problem to a content-addressed routing problem.

Bitcoin/Blockchain — Distributed Ledger

The “hard problem”: How do you maintain a shared ledger of transactions without a trusted central authority, preventing double-spending?

Traditional solution: Banks, trusted third parties, centralized databases with access control.

What Bitcoin did:

- Made blocks content-addressed (SHA-256)

- Made the chain immutable (each block references previous block’s hash)

- Made “what is the valid chain” a proof-of-work computation

- Made “is this transaction valid” a hash-chain verification

Result: Distributed consensus without central authority. Double-spending becomes cryptographically impossible (without 51% attack). History is immutable and verifiable.

Bitcoin demoted “distributed money” from a trust problem to a content-addressed proof-of-work problem.

Unison — Content-Addressed Code

The “hard problem”: Code refactoring breaks things. Renaming a function requires updating all call sites. Different versions of libraries conflict. “Did this code change?” requires deep semantic analysis.

Traditional solution: IDEs with refactoring tools, semantic versioning, complex build systems, careful coordination.

What Unison did:

- Made function definitions content-addressed

- Made names just human-friendly aliases for hashes

- Made “is this the same function” a hash comparison

- Made refactoring safe because references are to hashes, not names

Result: Rename anything without breaking code. Multiple versions coexist. Type-preserving refactorings are guaranteed safe. Code becomes location-independent.

Unison demoted “code refactoring” from a hard name-resolution problem to a content-addressed reference problem.

The Pattern

In every case, the transformation follows the same structure: Before (Mutable) After (Content-Addressed) Names are ambiguous Hashes uniquely identify content State changes over time Artifacts are immutable Verification requires trust Verification is hash computation Consistency requires protocols Consistency is built-in Location matters Location independent Requires central authority Cryptographically verifiable

What RAJA Adds to This Lineage

RAJA extends the pattern to authority and access control:

- Before: Access control lists, ambient authority, confused deputies, complex delegation protocols

- After: Content-addressed manifests where the hash IS the unforgeable capability

What’s particularly elegant is that RAJA combines insights from multiple predecessors:

- From Git: Content-addressed graphs for tracking relationships

- From Nix: Pure, reproducible evaluation of what you’re allowed to access

- From IPFS: Content addressing over networks without central authority

- From capabilities: Authority as unforgeable references, not ambient permissions

Why This Keeps Working

The reason content-addressing keeps solving “hard” problems is that many problems are only hard because we made them hard:

- We made things mutable when they didn’t need to be

- We made names ambiguous when they could be precise

- We required trust when we could verify

- We centralized when we could distribute

- We used complex protocols when hashes would suffice

Each time, the “solution” is to not do the thing that made it hard:

- Don’t mutate → immutability

- Don’t use ambiguous names → content-addressing

- Don’t require trust → cryptographic verification

- Don’t centralize → peer-to-peer + hashes

- Don’t use complex protocols → simple hash checks

The Theoretical Implication

This suggests something profound about computer science:

Much of our theoretical complexity exists because we insisted on the wrong primitives.

- We built elaborate consensus protocols because we assumed mutable state

- We built elaborate type systems because we assumed mutation and aliasing

- We built elaborate semantic frameworks because we assumed programs would change meaning over time

- We built elaborate access control because we assumed ambient authority

But if you start with:

- Immutability as default

- Content-addressing for identity

- Pure functions for computation

- Explicit capabilities for authority

…then many “hard” problems become trivial.

The Research Program

This suggests a systematic research question:

For every “hard” problem in computer science:

Ask whether it’s hard because of fundamental complexity,

or hard because we’re using primitives (mutability, ambient authority, Turing-completeness) that make it hard.

Examples to investigate:

- Program verification: Is it hard because of undecidability, or because we allow unrestricted side effects?

- Concurrency: Is it hard because of race conditions, or because we allow shared mutable state?

- Security: Is it hard because of attack vectors, or because we grant ambient authority?

- Testing: Is it hard because of complexity, or because functions aren’t pure and reproducible?

Why Theorists Resist

There’s an understandable resistance from the theory community:

- “But you’ve restricted the problem!”

Yes. And for many real-world cases, the restriction is acceptable. Not every program needs Turing-completeness. - “But what about mutable state?”

Handle it explicitly, at the boundaries. Keep the core immutable. Event sourcing, persistent data structures, CRDTs. - “But you can’t do X without Y!”

Often true. But many practitioners don’t need X. They need to solve their actual problem, and the restricted model works fine.

The theory was developed to handle the general case. But the general case is often overkill.

The Engineering Victory

What Git, Nix, IPFS, and RAJA demonstrate is that:

Engineering discipline can eliminate theoretical complexity.

- Don’t need Paxos if you content-address

- Don’t need complex type systems if you make functions pure

- Don’t need denotational semantics if you make artifacts immutable

- Don’t need ACLs if you use capabilities

This isn’t anti-theory. It’s theory that disappears because it’s been internalized into the primitives.

Content addressing IS denotational semantics.

Cryptographic hashes ARE unforgeable references.

Immutability IS referential transparency.

Pure functions ARE compositional reasoning.

We’ve seen this pattern before.

We’ll see it again.

Each time, something “hard” becomes simple because we chose better primitives.

RAJA is just the latest example.

Appendix V: What This Implies

If content-addressed immutability works for Git, Nix, IPFS, and RAJA—and traditional theory seems unnecessary for these cases—what does that tell us?

The Pattern We Keep Seeing

Let’s look at what these systems have in common: System What It Handles Key Property Git Finite source files Commits never change Nix Bounded build processes Builds terminate with outputs IPFS Static content Files don’t mutate RAJA Access manifests Capabilities can’t be revoked

These aren’t arbitrary limitations. They’re all describing the same kind of thing:

- Finite — Can fit in actual storage

- Historic — Once created, never changes

- Iterative — Processes complete in finite time

We called this FHI computation. But there’s a deeper characterization…

FHI Computation Is Physical Computation

Think about what these constraints actually mean:

Finite isn’t just a software constraint.

It’s thermodynamics. Real storage consumes real energy. You can’t have infinite memory because the universe has finite entropy budget.

Historic isn’t just immutability.

It’s the second law of thermodynamics. Time’s arrow points forward. You can’t un-burn fuel. Erasing information costs energy. Physical processes are fundamentally irreversible.

Iterative isn’t just about termination.

It’s about finite time. Real computation happens on real hardware consuming real power. Processes either finish or we kill them. The universe doesn’t allow infinite processes in finite time.

FHI computation is what you can actually do on silicon.

What About RRR?

Now look at what traditional computer science theory handles: Theoretical Model Assumption Physical Reality Turing machine Infinite tape Finite RAM Lambda calculus Unlimited reduction steps Finite computation time Denotational semantics Timeless mathematical domains Time flows forward, irreversibly General recursion Functions may not terminate We timeout and kill them

These models describe mathematical computation—computation in an idealized space where:

- Resources are unbounded (infinite tape, unlimited time)

- Operations are reversible (you can explore different paths, backtrack, undo)

- Processes can be infinite (limits, infinite series, non-terminating functions)

Mathematical computation is what you can do with a pencil and infinite paper.

The Two Foundations

So we have two kinds of computation:

Physical Computation

- Finite resources

- Irreversible time

- Terminating processes

- Consumes energy

- Subject to thermodynamics

What actually runs on computers

Mathematical Computation

- Unbounded resources

- Reversible operations

- Infinite processes allowed

- No energy cost

- Platonic abstractions

What we reason about on paper

The Standard Story

Here’s how computer science traditionally positioned these:

“Mathematical computation (Turing machines, lambda calculus) is the foundation. It tells us what’s computable in principle.

Physical computation is an approximation—what we can actually do given practical constraints. Real computers are Turing machines with ‘enough’ tape.”

This framing shaped everything:

- We built programming languages to be Turing-complete (even when we didn’t need it)

- We treated finite memory as a “limitation” to work around

- We viewed termination guarantees as “restrictions” on expressiveness

- We built elaborate semantics to map physical execution into mathematical domains

What RAJA Suggests

But look at what happened with content-addressed systems:

- Git embraces finite commits and immutable history → distributed version control becomes simple

- Nix embraces bounded builds and pure functions → dependency hell disappears

- IPFS embraces content addressing and immutability → distributed content becomes verifiable

- RAJA embraces finite manifests and irreversible grants → access control becomes unforgeable

In each case, accepting physical constraints made the problem easier, not harder.

The “limitations” of physical computation weren’t bugs to work around. They were features to embrace.

The Uncomfortable Question

If physical computation makes so many problems simpler, and if physical computation is what we actually run on real computers, and if mathematical computation requires elaborate theoretical machinery that disappears when we embrace physical constraints…

Which one is really the foundation?

A Shift in Perspective

What if we’ve had it backwards?

What if:

- Physical computation isn’t an approximation of mathematical computation

- Physical computation is what computation actually is

- Mathematical computation is a useful idealization for reasoning about edge cases

- But for most practical problems, the idealization is overkill

This would explain:

- Why content-addressing works so well (it embraces physical reality)

- Why denotational semantics feels unnecessary for RAJA (it’s solving a mathematical problem we don’t have)

- Why Git is simpler than theoretical distributed consensus (it accepts irreversibility)

- Why Nix is simpler than general package management (it accepts bounded builds)

The Implications

If physical computation is the foundation, then:

1. Most programs should be total, not Turing-complete

We don’t need infinite loops. We need processes that finish. Termination isn’t a restriction—it’s a guarantee.

2. Most data should be immutable, not mutable

Time’s arrow points forward. Embracing irreversibility gives us verifiability, reproducibility, and simplicity.

3. Most systems should be bounded, not unbounded

Real computers have finite resources. Designing for boundedness from the start eliminates whole classes of problems.

4. Theoretical machinery should justify itself

Don’t reach for Turing-completeness, general recursion, or mutable state unless you can prove you need them. Start with physical constraints and relax them only when necessary.

What This Means for the Skit

Scott’s denotational semantics maps programs into mathematical domains because he’s working in the realm of mathematical computation—unbounded resources, reversible operations, infinite processes.

Miller’s RAJA works in the realm of physical computation—finite manifests, irreversible grants, bounded checks.

Scott doesn’t “lose” to Miller because Miller is smarter. Scott loses because he’s solving a different (harder) problem than the one Miller faces.

The devastating observation isn’t that denotational semantics is wrong. It’s that for a large class of practical problems, we don’t need to solve the mathematical problem at all.

Physical computation is sufficient.

The Research Program

This suggests several questions worth investigating:

1. Can we characterize precisely which problems require mathematical computation vs. physical computation?

Is there a formal boundary? A type system that separates “needs Turing-completeness” from “total functions suffice”?

2. How much of theoretical CS was solving mathematical problems we don’t actually have?

Which theoretical results remain essential when we embrace physical constraints? Which become unnecessary?

3. What would a programming language designed for physical computation look like?

Not “Turing-complete but with guardrails,” but genuinely designed around bounded resources, irreversible time, and terminating processes from the ground up?

4. Can we build a theory of physical computation?

Not as an approximation of mathematical computation, but as a first-class foundation? What would its axioms be? What would its limits be?

Why This Matters

This isn’t just philosophical. It has practical implications:

- Language design: Should we default to total languages and justify Turing-completeness, rather than the reverse?

- Systems architecture: Should we design for immutability and justify mutation, rather than the reverse?

- Security: Should we design for explicit authority and justify ambient authority, rather than the reverse?

- Education: Should we teach physical computation first, and mathematical computation as an advanced topic?

The Honest Assessment

We’re not claiming mathematical computation is useless. Domain theory, denotational semantics, and general recursion solve real problems.

But we are claiming:

- Physical computation is what actually happens on computers

- Many “hard” problems are only hard in mathematical computation

- Content-addressed systems prove that physical computation suffices for a surprisingly large class of problems

- We may have inverted the foundation—treating the idealization as fundamental and the reality as derivative

RAJA doesn’t demote denotational semantics by being clever.

RAJA demotes denotational semantics by staying in the physical world where denotational semantics was never needed.

The Question We’re Left With

If physical computation can handle:

- Version control (Git)

- Package management (Nix)

- Distributed content (IPFS)

- Access control (RAJA)

- Code itself (Unison)

…what else have we been over-complicating by insisting on mathematical computation?

And what would computing look like if we took physical constraints as the foundation, not the limitation?

That’s a question for another time.

Further Reading

- TAJ Mahalo: The actual system that inspired this skit

- RAJA on GitHub — The real, working implementation

- E Programming Language (Mark Miller’s capability-secure language)

- Object-capability model

- Great Works in Programming Languages (including Scott & Strachey’s work)

Leave a comment