Sequel to Humanity As Rationalizing The Irrational: The HARTI Hypothesis

As Antonio Damasio, play up the metaphor of the apple in Genesis (“ye shall be as gods“) to reflect on how our naive faith in AI — and perhaps our worship of disembodied Platonism — is contradicted by C. Elegans.

ChatGPT prompt

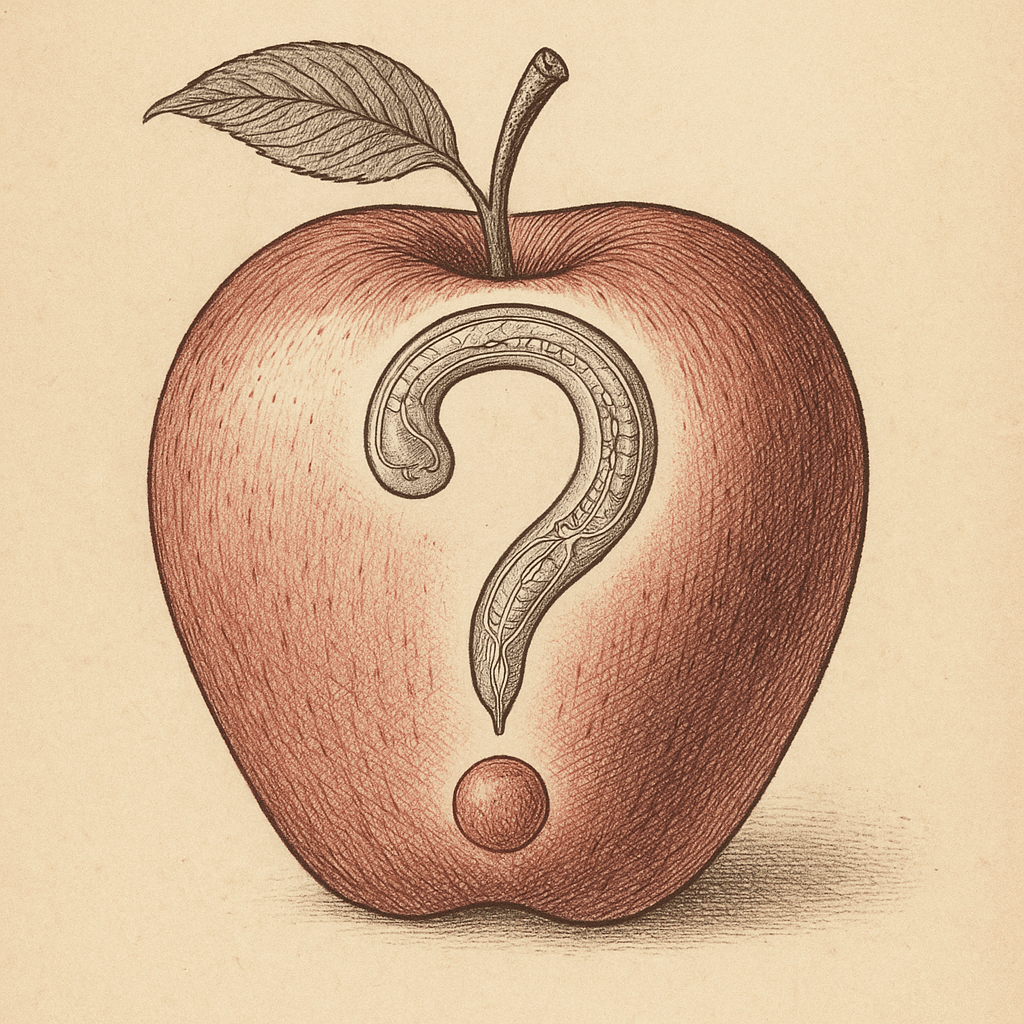

In the Book of Genesis, the apple is presented as the fruit of knowledge. To eat it is to reach for godlike powers — the capacity to judge, to reason, to know good and evil. The story has been told for millennia as a parable of ambition and its consequences.

Today we are once again offered an apple. This time, the promise is not delivered by a serpent but by technology. Artificial intelligence is the apple of our age. We are told that if we consume it, if we trust it, we will become as gods: thinking faster, reasoning deeper, free of error, and perhaps even free of our biology.

But the apple, then and now, has a worm.

The Misconception of Reason as Essence

For centuries, Western philosophy has privileged reason. From Plato to René Descartes, mind has been imagined as a pure, disembodied faculty. The body was seen as a distraction, or worse, a prison.

This philosophical inheritance lingers in the way we imagine artificial intelligence. We assume that because AI can manipulate language and symbols, it is approaching the essence of the human mind. The myth of “superintelligence” is built on this assumption: that what matters most in cognition is reason, and reason can be separated from embodiment.

The myth of “superintelligence” is built on this assumption: that what matters most in cognition is reason, and reason can be separated from embodiment.

But biology tells a different story.

The Worm as Counterexample

Consider Caenorhabditis elegans, a nematode with just 302 neurons. With so little neural material, one might expect a narrow repertoire. And yet the worm senses and responds to gradients of food and temperature; it integrates hunger, fatigue, and stress; it navigates its world and even exhibits sleep-like states.

There is no disembodied “reason” in this creature. There is only cognition in the most fundamental sense: an organism managing the business of its life, moment to moment, in constant dialogue with its body and environment.

There is no disembodied “reason” in this creature. There is only cognition in the most fundamental sense…

If a worm requires all its neurons for embodiment, what does that say about us? Out of our billions of neurons, how many are dedicated to abstract thought? Very few. The overwhelming majority are devoted to homeostasis, sensation, movement, and emotion. Reason is real — but it is a thin layer upon a vast ocean of embodied processes.

The Worm in the Apple

The myth of superintelligence assumes that if we amplify reason, we capture mind. That is the apple we are offered: shiny, perfect, Platonic. But the worm inside — the actual worm — reminds us that intelligence is not reducible to reason. It is inseparable from life.

…intelligence is not reducible to reason. It is inseparable from life.

Embodiment is not an afterthought. It is the ground from which reason emerges. Disembodied intelligence, however powerful in calculation or language, lacks the substrate of feeling, the regulation of homeostasis, the anchoring of consciousness in a living body.

A Cautionary Reflection

Artificial intelligence is a remarkable achievement. It can extend our capacity to reason, to analyze, to manipulate symbols. But we should resist the temptation to equate these capacities with the fullness of human cognition. To do so is to mistake the rind for the fruit.

The lesson of the worm is simple: intelligence is an activity of the living. Without the body, there is no mind. Without feeling, there is no consciousness. The apple of superintelligence may glisten, but if we bite too uncritically, we risk forgetting the worm that gives it substance.

The lesson of the worm is simple: intelligence is an activity of the living.

Conclusion

In Genesis, the apple brought a fall. In our own age, the apple of superintelligence need not. But only if we remember that reason, however brilliant, is not the essence of the mind. It is an accessory of life.

Inside the apple, there is always a worm.

Appendix: Non-Living Intelligence

Clarify that non-living systems literally “have intelligence” — information that can be used to make decisions. But to “be intelligent” requires embedding in an (appropriate!) system that experiences the consequences. Which (as we are discovering with context engineering) is where the really hard work (and actual benefit) come in.

ChatGPT prompt

It is not quite right to say that non-living systems lack intelligence.

- Viruses carry highly structured information in their genomes. That information encodes strategies that, once enacted, let them outmaneuver hosts.

- Computers and algorithms hold rules, weights, and data structures that can process information and generate outcomes.

In this sense, non-living systems have intelligence: they contain information that can be used to make decisions.

Being Intelligent

To be intelligent requires something more. It requires that this information be:

- Embedded in a system that interacts with an environment.

- Coupled to consequences for persistence or failure.

- Integrated through feedback so that decisions are evaluated and adapted in light of outcomes.

- A virus has intelligence in its genome, but it only becomes intelligent when embodied in a host cell where consequences play out.

- A computer program has intelligence in its code, but it only becomes intelligent when situated in a broader system — whether that system is an organism, a society, or (as we are discovering in context engineering) an interface that supplies feedback, constraints, and goals.

Why This Matters

The really hard work of intelligence is not storing or even manipulating information. It is embedding that information in a system that cares about outcomes — that experiences success and failure, persistence and dissolution.

The really hard work of intelligence is not storing or even manipulating information.

It is embedding that information in a system that cares about outcomes — that experiences success and failure, persistence and dissolution.

That is where intelligence becomes real, and where the actual benefits of intelligence emerge.

Takeaway

- Non-living systems have intelligence insofar as they encode information and strategies.

- Systems only are intelligent when that information is embodied in a context where consequences matter.

- The work of building such contexts — whether in biology or in AI — is where the frontier lies.

Leave a comment