Julia Freeland Fisher (on Class Disrupted) puts her finger on the real existential risk of AI: ensuring we prioritize human connection over simulated experiences.

A Language With No ‘=’: My Journey to Homoiconic C

came of age in the 1980s, as the C programming language and UNIX operating system were becoming the gold standard for "serious" computing. I was taught that: - Lisp reflects how computers **think** - C reflects how computers **work** - Shell scripts reflect how humans **write** I never questioned this split ....

Want Missional Pioneers? Build Hohlraums (ChatGPT as Paul Graham)

Missional pioneers don’t fail because they lack vision. They fail because they lack a structure that provides both gritty grace and painful kindness—the two forces required to trigger transformation. They need hohlraums…

Searching for Stability: Celestial Holography and the Origin of Spin

Through celestial holography, we can reinterpret spin and angular momentum as emergent from the conformal symmetries of the celestial sphere. This approach offers a novel and potentially unifying principle that aligns with the ideas proposed by Witten and colleagues, providing a fresh lens to understand the stability of the universe.

The Sixth Loop: Ultimate Causation?

Brahman: "You have seen how the loops of causation evolve, each encompassing new dimensions of reality. Now, I challenge you to identify what lies beyond Status—what is the Sixth Loop? Is it grounded in mind, consciousness, technology, or something even more profound?"

The Fifth Loop of Universal Causation: Status

Athena: Humanity has mastered the physical, thrived biologically, developed language to shape meaning, and built narratives to create purpose. But beneath it all lies a more primal force: Status. Is this the hidden engine of causation, organizing hierarchies, influencing behavior, and even steering entire civilizations? Let’s discuss.

CTMU: A Cognitive-Theoretic Message to University Graduates on Meaningful Life

As you leave this chapter of your life and step into the next, remember: the CTMU shows us that life is not random. It is meaningful, structured, and full of potential. You have the tools to shape your destiny, to contribute to the coherence of the world, and to live a life of purpose.

TSM-11: The Next WAVE of Computing — Whole Architecture Validating Encoders

WAVEs promise to redefine how we design, optimize, and deploy applications by tightly coupling software and hardware in ways previously unimaginable. With WAVEs, developers can create applications without worrying about hardware constraints, while the WAVE ensures the resulting design is perfectly mapped to hardware optimized for power, performance, and efficiency.

TSM-10.1: HLIR – Homoiconic, High-Level Intermediate Representation

instructions in a homoiconic form. It represents a novel synthesis in compiler design by bridging the gap between human and machine representations of programs. By combining monadic composition with homoiconic structure, HLIR allows developers to express computational intent with minimal syntax while maintaining direct mappings to MLIR's powerful optimization framework. This marriage of high-level semantics with low-level compilation produces a uniquely ergonomic intermediate representation - one where code is data, transformations are first-class citizens, and optimization becomes natural rather than imposed. The result is a language that is both easy for humans to reason about and efficient for compilers to transform, potentially setting a new standard for intermediate representations in modern compiler design.

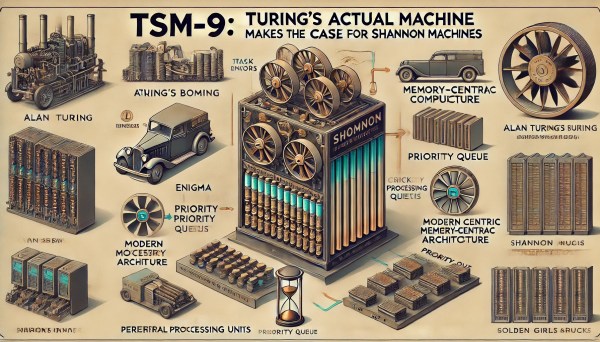

TSM-9: Turing’s Actual Machine Makes the Case for Shannon Machines

In a sense, the Bombe makes the case for Shannon Machines by showing how computation in the real world is defined by constraints—bounded memory, time-sensitive tasks, cooperative components, and structured data access. Turing’s actual machine, the Bombe, reminds us that effective computation is often about meeting specific needs within specific limits. Rather than the theoretical purity of infinite tape, Turing’s Bombe—and by extension, Shannon Machines and Golden Girls Architecture—illustrate how real computation can be collaborative, memory-centric, and bounded by design.

You must be logged in to post a comment.