As a optimistic analog of Henry M. Littlefield, explore Hadestown as a metaphor for not just self-alienation but potential reconciliation in an industrializing age — as liminal as our own transition to an AI economy.

ChatGPT Prompt

Incorporate Venkatesh Rao’s sobering observation that “civilization is the process of turning the incomprehensible into the arbitrary”; agrarian scarcity as more authentic yet more brutal than its industrial successor.

I. Hadestown as the Industrial Transition

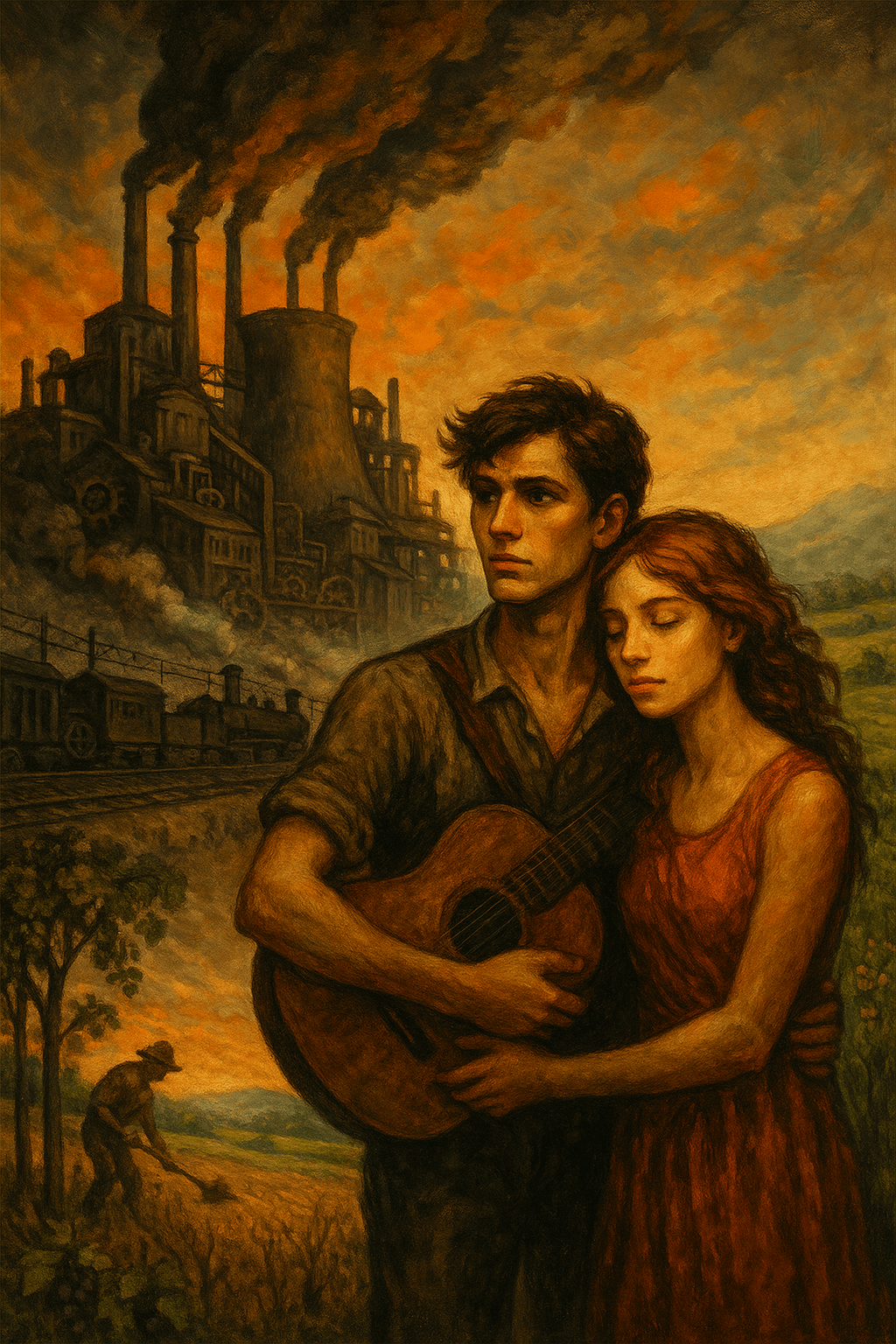

Hadestown is a factory-town dystopia—an echo of industrialization’s dehumanizing force. It runs on discipline, not spontaneity; on walls and rules rather than fields and risk. Eurydice, driven by scarcity, trades her freedom for security—a trade not unlike those made during the agrarian-to-industrial shift: surrender to the “Company Town,” the factory, the schedule.

But here’s the Littlefield-style twist: Hadestown is also the site where reconciliation becomes possible. Unlike the surface world where nature is unpredictable, and “the wind comes up and blows you down,” Hadestown offers order. It is not a death, but a stasis—where things can be negotiated, even if the price is high. It is where the gods are reachable, and where Orpheus can plead his case.

Much like our AI-driven world: governed by invisible algorithms, hyper-efficiency, and optimization. We are trading the “incomprehensible”—the divine unpredictability of nature and human whim—for the “arbitrary”: inscrutable decisions made by AI, opaque bureaucracies, and systems that no one wholly understands. Venkatesh Rao’s point stings here: civilization always smooths mystery into mechanism. But the same system that erodes magic also stabilizes chaos.

Venkatesh Rao’s point stings here: civilization always smooths mystery into mechanism. But the same system that erodes magic also stabilizes chaos.

II. Agrarian Brutality vs. Industrial Alienation

Rao suggests a difficult truth: that the world of pre-modern scarcity was more authentic, even if more brutal. In Hadestown, the world above is more free, more wild, but also terrifying. Hades’ promise is grim, but seductive:

“A wall keeps out the enemy / And we build the wall to keep us free.”

It echoes the logic of industrial modernity—and perhaps today’s AI logic as well: automate to ensure efficiency, optimize to reduce suffering, surrender freedom for predictability.

And yet, within Hadestown, something stirs: the memory of song. Orpheus brings not just a plea, but a melody—a symbol of myth, narrative, and the human capacity to imagine a different world. If AI is the next Hadestown—efficient, secure, but potentially dehumanizing—then Orpheus is the mythmaker, the artist, the remixer. A reminder that we are still here, and that meaning can emerge even inside the machine.

Orpheus brings not just a plea, but a melody—a symbol of myth, narrative, and the human capacity to imagine a different world.

III. Reconciliation Through Repetition and Liminality

Hadestown’s cyclical structure—“it’s a sad song, but we sing it anyway”—speaks to a deeper truth: transformation doesn’t come in one act, but in repetition, iteration, and trust. Orpheus fails, yes—but the song gets sung again. Every performance is a liminal space: between failure and hope, between machine and myth, between economy and ecology.

Every performance is a liminal space: between failure and hope, between machine and myth, between economy and ecology.

In our transition to the AI age, we too occupy a liminal space. We’re not fully in the old world of human labor and scarcity, nor in the post-scarcity AI utopia some imagine. We are Eurydice—hungry, afraid, and tempted. We are Orpheus—idealistic, uncertain, singing into the void. And we are Hades and Persephone—rulers trying to balance order and chaos, power and love.

Hadestown offers no neat resolution, but it does offer an emotional reconciliation. In recognizing our liminality, it suggests that hope lies not in a return to Eden or a leap into utopia, but in remembering the song: the stories that make us human, the myths that guide meaning, the courage to look back and still walk forward.

IV. Conclusion: Singing Into the Algorithm

If, as Rao says, civilization trades the incomprehensible for the arbitrary, then Hadestown reminds us we can still smuggle soul into the system. In an AI-driven future, reconciliation may not come through revolution, but through retuning the system—embedding empathy, story, and human memory into the code.

If, as Rao says, civilization trades the incomprehensible for the arbitrary, then Hadestown reminds us we can still smuggle soul into the system.

Orpheus fails. But he tries again.

And so do we.

Epilogue: A Note on Form

In Anaïs Mitchell’s Hadestown, we are drawn into a mythic world of love and loss, tyranny and resistance—a folk-opera reimagining of the Orpheus and Eurydice myth. At first glance, Hadestown appears as a warning: the underworld is industrialized, cold, and exploitative; love fails; memory fades.

Yet, like Henry M. Littlefield reading the Wizard of Oz as a parable of Populist-era tensions, Hadestown can also be viewed as an allegory for transformation and—crucially—reconciliation in a transitional age. It offers not only a critique of power and progress but a vision of healing: between the individual and society, nature and machine, memory and myth.

Leave a comment