Sequel to Diaphorum 4: The Broken Triad (Aristotle’s Architectonic “Trinity”)

How the Logos Became Immanent, and Made Us Immortal

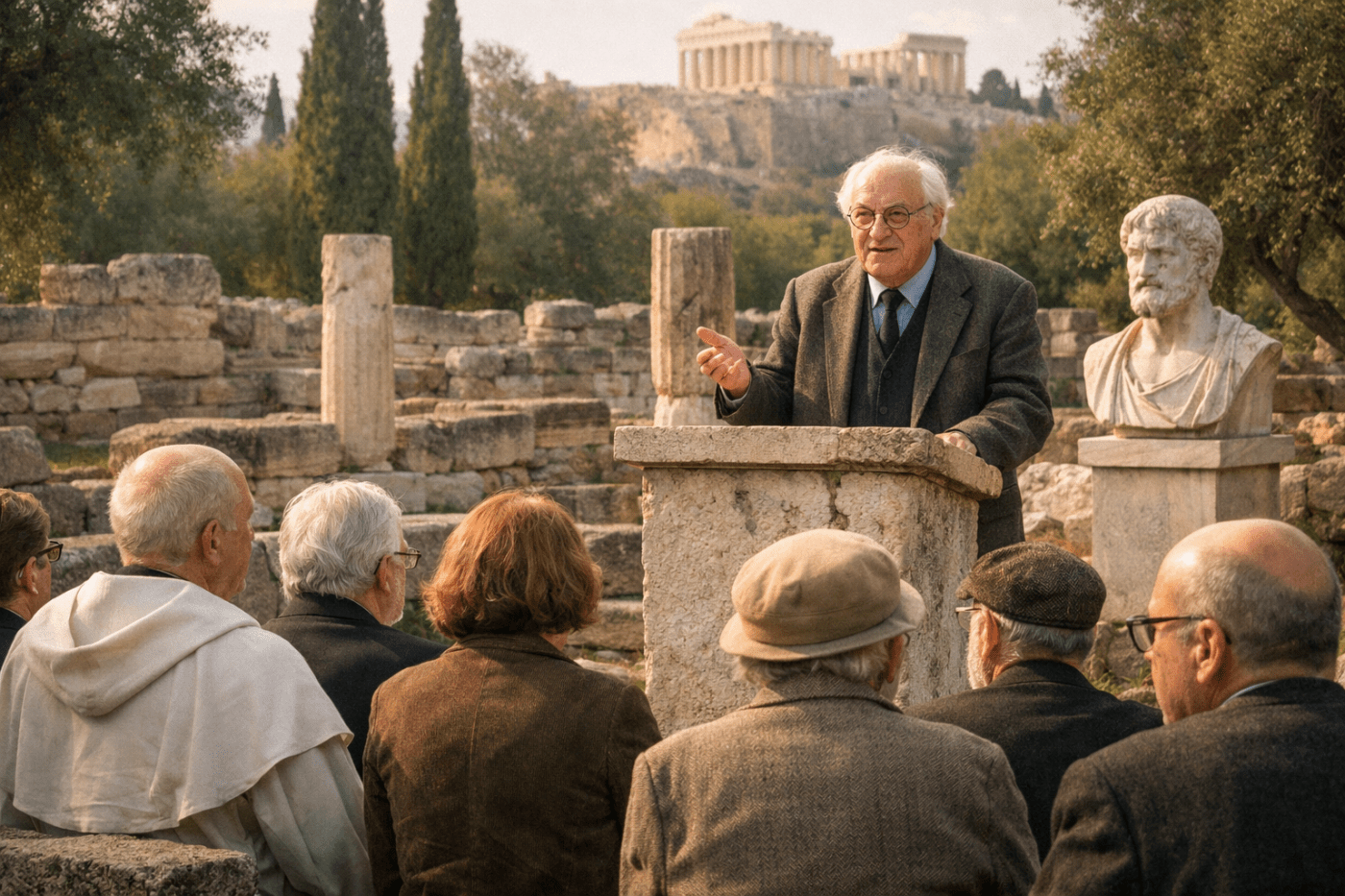

As Hans-Georg Gadamer, write a spoiler-free eulogy about how Aristotle’s integration of Socratic skepticism and Platonic idealism made modern life possible.

ChatGPT Prompt

1. Prologue: Gratitude Before Interpretation

There are thinkers whose work demands critique, and others whose work first demands thanks. Aristotle belongs decisively to the latter. Before we interpret him, before we amend him, before we enlist him in later quarrels, we owe him gratitude—for making the world habitable by understanding.

This is not small praise. It is civilizational.

[That this gratitude can still be articulated at all is due in no small part to Hans-Georg Gadamer, who taught us to approach tradition not as an obstacle to truth but as the medium in which truth becomes possible.]

2. The Glad Tidings: Meaning Is Here

Aristotle’s good news can be stated simply:

- being is intelligible

- intelligibility is immanent

- the world does not need to be escaped to be understood

Against the suspicion—already present in Plato—that truth lives elsewhere, Aristotle teaches us to stay. He does not ask us to look past things, but to look long enough. In doing so, he restores dignity to attention itself. The patient gaze becomes a moral act.

This is a gospel because it liberates: it frees us from the fear that reality will dissolve under scrutiny.

3. Logos at Home in the World

Aristotle’s logos does not descend as a foreign law. It dwells—quietly, faithfully—within nature as form, cause, and end (telos). To understand is not to impose but to receive articulation from what is already speaking.

Here Aristotle achieves something rare: he unites explanation with reverence. Knowledge does not conquer its object; it participates in it. This participation is not mystical in the pejorative sense. It is disciplined, public, and teachable.

In this way, Aristotle rescues reason from arrogance without surrendering it to skepticism.

4. Seeing as Participation

The highest human activity Aristotle names theōria—contemplative seeing. This seeing is not withdrawal; it is communion. When the intellect apprehends form in matter, it does not leave the world behind. It joins what endures within the world.

To see truly is already to share in what lasts.

This is the sense in which Aristotle dares to speak of the intellect (nous) as immortal—not as personal survival or metaphysical escape, but as participation in intelligibility that does not perish. In acts of genuine understanding, time loosens its grip. We are not saved from finitude; we are addressed beyond it.

5. The Courage of Trust

What deserves our deepest respect is the courage implicit in Aristotle’s posture. He trusts that:

- the world is not deceptive

- meaning is not fragile

- truth can withstand patient inquiry

Such trust is not naïve. It is earned against the background of myth, superstition, and despair. Aristotle builds a home for understanding in which inquiry can proceed without panic. This invulnerability is not denial; it is scaffolding—the necessary stability without which later risks would be unthinkable.

6. Tradition as a Living Medium

Here we glimpse what Gadamer famously called wirkungsgeschichtliches Bewusstsein—historically effected consciousness. Aristotle does not give us conclusions to repeat; he gives us a way of inhabiting understanding. His work teaches us how to listen, how to discriminate, how to let things show themselves.

Tradition, in this sense, is not a burden but a medium. Aristotle’s gospel teaches us to trust that medium long enough for understanding to become possible at all.

7. Why This Gospel Had to Be Invulnerable

An invulnerable gospel is not a failure of nerve; it is an act of care. Before the world could be tested, it had to be trusted. Before understanding could risk itself, it had to be at home.

Aristotle’s achievement was to make that home durable. He stabilized meaning so that inquiry could continue, generation after generation, without collapsing into either dogma or despair.

8. Eulogy, Properly Spoken

A eulogy does not say, “You were insufficient.” It says, “Because you lived, we could live next.” Aristotle’s Invulnerable Gospel gave us a world that could be contemplated without fear and a logos that could dwell in flesh without scandal.

For this, we owe him more than critique. We owe him thanks.

9. Final Benediction

Let us say it plainly and without qualification:

Aristotle taught us that by learning to see, we already participate in what does not pass away.

That teaching did not end philosophy.

It made philosophy possible.

Appendix I: Mini-Eulogies by Others

A Chorus of Gratitude for Aristotle’s Invulnerable Gospel

A. Thomas Aquinas — The Faithful Receiver

Thomas Aquinas would say simply:

Aristotle taught us how to trust that being can be understood without being escaped.

Without that trust, theology itself would have had no grammar.

For Aquinas, Aristotle is not the one who erred, but the one who prepared a world in which truth could safely dwell. He gave reason enough stability that faith would not have to fight it. That alone is sanctifying.

B. Alasdair MacIntyre — The Moral Architect

Alasdair MacIntyre would praise Aristotle as the last thinker to show us how a life, a practice, and a tradition can cohere.

Aristotle made it possible to believe that practices aim at goods internal to themselves,

and that a shared logos can sustain a community across generations.

Without Aristotle’s confidence in immanent ends, modern moral life would have collapsed into managerial technique or emotivism long before it actually did.

C. Josef Pieper — The Liturgist of Seeing

Josef Pieper would write a quiet, luminous paragraph and then stop.

Aristotle taught us that leisure is not idleness but affirmation.

To contemplate is already to say “yes” to being.

Pieper would thank Aristotle for teaching us that seeing is already a form of praise, and that a world which can be contemplated is already, in some measure, redeemed.

D. Hannah Arendt — The Defender of the World

Hannah Arendt would honor Aristotle for grounding amor mundi—love of the world—before politics, action, or judgment.

Aristotle preserved the dignity of the common world by insisting that it could be understood,

spoken about, and shared.

Before we could act responsibly in the world, we had to believe the world was there to be seen together. Aristotle made that belief plausible.

E. Iris Murdoch — The Moral Seer

Iris Murdoch would offer this as her eulogy:

Aristotle understood that goodness is not made by will but discovered by attention.

He taught us that just seeing clearly is already a moral achievement.

For Murdoch, Aristotle’s invulnerable gospel is the conviction that attention itself participates in the Good, without drama, without heroics.

F. A Contemporary Scientist (Anonymous)

A modern scientist, standing quietly at the back of the Lyceum, might say:

Aristotle taught us that the world would not shatter if we looked closely.

Without that confidence, no experiment would ever have been dared.

The patience of observation precedes the courage of intervention.

G. Closing Choral Line

Together, these voices say—not in unison but in harmony:

Aristotle gave us permission to believe that reality could bear our attention.

Only because of that gift could later ages risk disappointment, error, and change.

That is not an invulnerable legacy.

It is a foundational one.

Appendix II: Why This Is a Eulogy

1. A Eulogy Is Not a Refutation

This text is called a eulogy because it does not arise from disagreement, but from indebtedness.

A refutation seeks to show where a thinker failed.

A eulogy seeks to name what would be missing if that thinker had never lived.

To write a eulogy for Aristotle is to speak from inside a world he made possible, not above it.

2. Eulogies Are Written After Succession

A eulogy is only possible once inheritance has occurred.

We do not eulogize what we have not yet outgrown, nor what we have rejected in bitterness. We eulogize what has done its work—what carried us far enough that we could eventually walk differently.

This text assumes:

- Aristotle’s work succeeded

- it succeeded so deeply that it disappeared into our way of seeing

- and that modern life is unintelligible without it

That is the mark of something worth eulogizing.

3. Because the Gospel Worked

This is a eulogy because the Invulnerable Gospel did what it needed to do.

It taught humanity that:

- the world is intelligible

- attention is trustworthy

- meaning does not flee inquiry

- logos can dwell in what is

Before there could be risk, there had to be trust.

Before there could be action, there had to be sight.

Aristotle gave us that sight.

4. Because We No Longer Need It in the Same Way

A eulogy is spoken when something is no longer asked to carry the whole weight of the present.

Aristotle’s gospel no longer bears that burden—not because it failed, but because it succeeded so thoroughly that it made new postures possible.

We can now risk:

- error

- disappointment

- intervention

- revision

only because Aristotle first stabilized meaning.

That transition—from necessity to gratitude—is precisely when a eulogy becomes appropriate.

5. Because Critique Without Gratitude Is Incoherent

Every critique presupposes a ground from which it speaks.

This text refuses the incoherence of criticizing Aristotle for not giving what only later history could even imagine. It speaks instead from the recognition that:

what we now see differently is only visible

because someone first taught us how to see at all.

That is not indulgence.

That is intellectual honesty.

6. Because Eulogies Name Gifts, Not Gaps

This appendix exists to make explicit that the purpose of the text is not to highlight what Aristotle lacked, but to name what he gave:

- a world safe enough to study

- a logos gentle enough to listen

- an intellect confident enough to trust seeing

- a conception of immortality grounded in participation, not escape

These gifts do not expire when they are surpassed.

They remain foundational.

7. Because Love Precedes Judgment

A eulogy speaks from love, not verdict.

It is written by those who no longer need a thinker to be wrong in order to move forward. It says:

we are here because you were here

and that is enough

This posture is not anti-critical.

It is post-defensive.

8. Final Clarification

This is a eulogy because it says:

- thank you before but

- inheritance before revision

- gratitude before difference

Only from that order can anything new be said without ingratitude or distortion.

9. Closing Line

If this appendix must end with a single sentence, let it be this:

A eulogy is written not when something is disproven, but when it has finally been loved enough to be laid to rest with honor.

That is why this is a eulogy.

Appendix III: Aristotle on Learning

How Seeing, Listening, and Experience Make Understanding Possible

1. Learning as a Human Capacity, Not a Technique

For Aristotle, learning is not primarily a method but a mode of participation in what is. To learn is not to manufacture knowledge, but to allow what is intelligible to show itself to a properly formed intellect.

This already distinguishes Aristotle from both:

- technical instruction (techne), and

- rhetorical persuasion (sophia in its sophistic sense).

Learning, for Aristotle, is the slow education of attention.

2. Learning by Seeing: Empeiria and Observation

Aristotle places extraordinary weight on empeiria—experience.

Learning begins with:

- repeated perception

- careful observation

- patience with particulars

From the Posterior Analytics onward, Aristotle insists that universals do not descend from heaven; they emerge from lived contact with particulars. Nature must be watched long enough to disclose its patterns.

This is why Aristotle:

- catalogues animals,

- studies motion,

- classifies regimes,

- attends to ordinary speech.

Seeing, here, is already a disciplined practice.

3. Learning by Listening: Akroasis and Tradition

Equally important is what Aristotle effectively invents as a philosophical category: learning by listening (akroasis).

In ethics especially, Aristotle emphasizes that:

- one must be brought up well

- instructed by those already formed

- inducted into practices before judging them

Learning is therefore tradition-mediated. The learner does not stand outside the world of meaning but is received into it.

This anticipates what Hans-Georg Gadamer would later articulate as wirkungsgeschichtliches Bewusstsein: understanding is always historically effected.

4. Habituation: Learning Before Knowing

In the Nicomachean Ethics, Aristotle makes a decisive claim:

We become just by doing just acts.

Virtue is not learned by theory but by habituation (ethismos). One must act rightly before one can fully understand what rightness is.

This is crucial:

- action precedes articulation

- formation precedes reflection

- practice precedes principle

Here Aristotle comes very close to affirming learning by doing—though he frames it primarily in moral, not epistemic, terms.

5. The Birth of Nous: From Experience to Insight

At the center of Aristotle’s account of learning stands nous—the intellect that apprehends first principles.

Aristotle is explicit:

- nous cannot be taught directly

- it is not deduced

- it emerges from experience

Repeated perception → memory → experience → nous

This progression is one of Aristotle’s most important legacies. Insight is not downloaded; it condenses.

Learning culminates not in certainty, but in seeing what had been there all along.

6. What Aristotle Refuses to Say

What Aristotle does not quite say is just as important.

He does not say that:

- error generates first principles

- failure teaches more than success

- intervention is epistemically primary

- first principles can be shattered and reborn

Learning refines vision; it does not rupture it.

For Aristotle, nous awakens through accumulation, not collision.

This restraint is not blindness—it is care.

7. Why This Account Was Necessary

Aristotle’s account of learning makes possible:

- education without coercion

- inquiry without panic

- tradition without dogmatism

- confidence without hubris

By grounding learning in seeing and listening, Aristotle stabilizes meaning long enough for understanding to become trustworthy.

Before learning could be experimental, it had to be credible.

8. Learning as Participation in What Endures

Because learning culminates in nous, and nous apprehends what is universal, Aristotle can say that learning is a form of participation in what does not pass away.

This is why:

- contemplation is the highest activity

- seeing is already a kind of fulfillment

- learning has an implicitly ethical and metaphysical dignity

To learn is not merely to acquire information, but to share in intelligibility itself.

9. Why This Still Matters

Even where later traditions will emphasize:

- experimentation,

- error,

- disruption,

- intervention,

they do so on ground Aristotle prepared.

Learning by doing presupposes:

- something worth doing to

- a world that will answer

- a reality that can be trusted not to dissolve

Aristotle taught us to trust learning enough to risk it later.

10. Closing Line

If this appendix must end with a single sentence, let it be this:

Aristotle taught us that learning begins in attention, matures through habit, and culminates in seeing what was always already there.

That vision remains indispensable—even where it is no longer sufficient.